Who Should Be Efficient with AI in Schools? Part 1: The Why.

Why student AI use can’t copy adults for the purpose of efficiency.

Summary

Two-part series: theory first, practice second. Adults use AI for efficiency; students risk cognitive debt if they copy them. Instead of banning AI in K-12 classrooms, design learning-first workflows. To protect productive struggle, use AI to remove real barriers, and require small “breadcrumbs” of thinking plus a quick check to ensure AI supports learning rather than replacing it.

Intro

As we begin 2026 and look back at 2025, Marc Zao-Sanders’ viral HBR piece was a helpful reality check and numerous social posts focused on AI for “therapy” and “finding purpose”. Here’s another great article from the NY Times about a proliferation fo children’s toys that serve as companions as well. While, what Jason Prohaska calls Artificial Imtimacy, hasn’t quite proliferated our classrooms, I want to wrap 2025 with a topic that I see mattering most for classrooms: teachers and students are using AI to save time: drafting, planning, summarizing, organizing, polishing, creating. Most everyday K-12 use is still about efficiency.

But K-12 students can’t simply inherit adult habits under the banner of competitiveness or staying up with technology. Every adult expert earned their literacy in a fully non-AI childhood; kids in 2025 are growing up inside an experiment and the long-term impacts of AI are in education are not clear. But what I can say is that the habits we practice with kids today will become the habits they practice as adults. For students who are learning to drive their own brains, “efficiency” can replace the struggle that builds judgment and reinforce shortcuts disguised as polished work. This post argues that student AI use must be fundamentally different from adults’. We should design thinking-first, scaffolded processes that build durable strategies for problem-solving, self-knowledge, connection-making, and reasoning, and bring AI in only when it supports cognitive moves.

Humans in Wall-E vs. Iron Man

This year, I read several amazing books that influenced how I approach AI. Funnily enough, all of them are about pedagogy and learning sciences that are pre-AI. And I’m finding that I am cementing a conclusion from last year: when we understand the learning sciences, how our brains develop, and research-backed pedagogy, then we can invite AI into the classroom because it should always be a learning-first approach centered around our children. In other words, what’s best for them? How can AI support what our kids need?

One of the books I read this year was Carol Dweck’s Mindset. In this seminal book (from 2007!), she argues that the mindset that we bring into our classrooms (growth vs. fixed) can have a significant impact on our ability to learn and grow. I think that today, many people take these concepts as granted, so instead of trying to convince you of their validity, I’d like to ask, what mindset is important when we use AI? I believe there are two mindsets toward AI:

The assistant mindset: AI is there to complete things for me.

The collaborator mindset: AI is there to complete things with me.

To understand these two mindsets, there are two films that I think explore both in kid-friendly language, so please feel free to share these ideas with your learners.

In the film Wall-E, humans have become so reliant on technology to do everything for them, that they have physically atrophied. They float in chairs, distracted by screens, unable to walk when falling out of their hover chairs (see image below).

Applying this AI as an assistant mindset to the classroom, I believe that it can surface when we think of school as a series of tasks we have to complete, and the shortest pathway with the fewest bumps is the best. In that way, learners with this mindset might use AI as a tool to cognitively offload their thinking , which, when done repeatedly, can lead to inadvertent cognitive atrophy much like the humans in Wall-E who forget how to walk. And as for us teachers, we might be supporting this very mindset when we choose to, perhaps through inaction or avoiding honest dialogue about AI, design learning tasks that see the deep, effortful thinking as secondary.

Deep, slow thinking sounds great, but realistically speaking, no human is engaged in effortful thinking all the time. Deep cognition requires work and energy as one of my favorite books by Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, explains. Our brains often prefer mental shortcuts, or heuristics as he calls them, to conserve effort and energy. I am really not doing this amazing book justice, so go read it and find out more. Glossing over it, the simple takeaway for schools is this: humans are already predisposed to avoid effort in a pre-AI world, and generative AI makes bypassing effort even more accessible, and even accidentally possible.

I want to propose that we, as educators, focus on developing humans who have AI-based skills they can use as strategies to support their thinking throughout their adult lives as a form of digital literacy. I also want to propose that we support children through scaffolded processes that name the thinking and make it clear when and how AI can (or cannot) be used at different steps.

In this more collaborative approach, I believe we can construct something that looks more like Marvel’s Iron Man. The genius creator, Tony Stark, is not replaced by the AI he creates (JARVIS); he is the pilot. The AI gives him strength, and the agency remains with him to decide how to solve problems. He battles villains and flies, something no human could do before. In Wall-E, humans lose something that makes them fundamentally human, the ability to walk. With Tony Stark’s flight, he transcends what it means to be human.

This is the goal of my book, AI-Enhanced Processes (second edition currently in review for publishing on Amazon, stay tuned). We want students to collaborate with AI, not be dependent on it to function.

Classroom dialogue ideas

Do you want to be carried by the chair in Wall-E or do you want to fly like Tony Stark? How can we think of AI as a collaborator or a superpower when we use it on this assignment?

Kids Need Productive Struggle

Learning to learn, the importance of effort, and developing study skills are age-old topics, but it’s worth repeating again in this AI context: that we need to teach students how to recognize what is and is not learning, how it can feel like a struggle, and help them see that they are learning.

I would argue that a core part of AI literacy is knowing what learning feels like: being able to tell when learning is actually happening. Students need both the big picture (why we go to school) and the immediate purpose (why are we doing this task), plus a practical question: How do I know I’m making progress toward mastery (constant and ongoing feedback loops)? When students can see evidence of improvement, they can make wiser choices about when AI is helpful and when it becomes unhelpful cognitive offloading.

Cognitive offloading is tempting because our brains are constantly weighing cost versus payoff. When effort doesn’t produce detectable progress, it starts to feel wasted, and shortcuts become more appealing. Imagine what’s going through a kid’s brain when he knows AI can produce a polished result instantly.

That brings me to an idea that’s sticking with me in 2025: AI-induced cognitive debt. When AI removes the thinking in the present moment (because it’s there, and the task feels low-value) students may gain a clean output, but they pay later in weaker recall, shallow understanding, and lower confidence when they’re on their own. They “owe” the thining to the AI they used for the perceived learning. You see it when students only read summaries instead of grappling with full texts, submit writing with minimal revision (more “reading an answer” than writing to think), or copy correct equations without attempting the reasoning first.

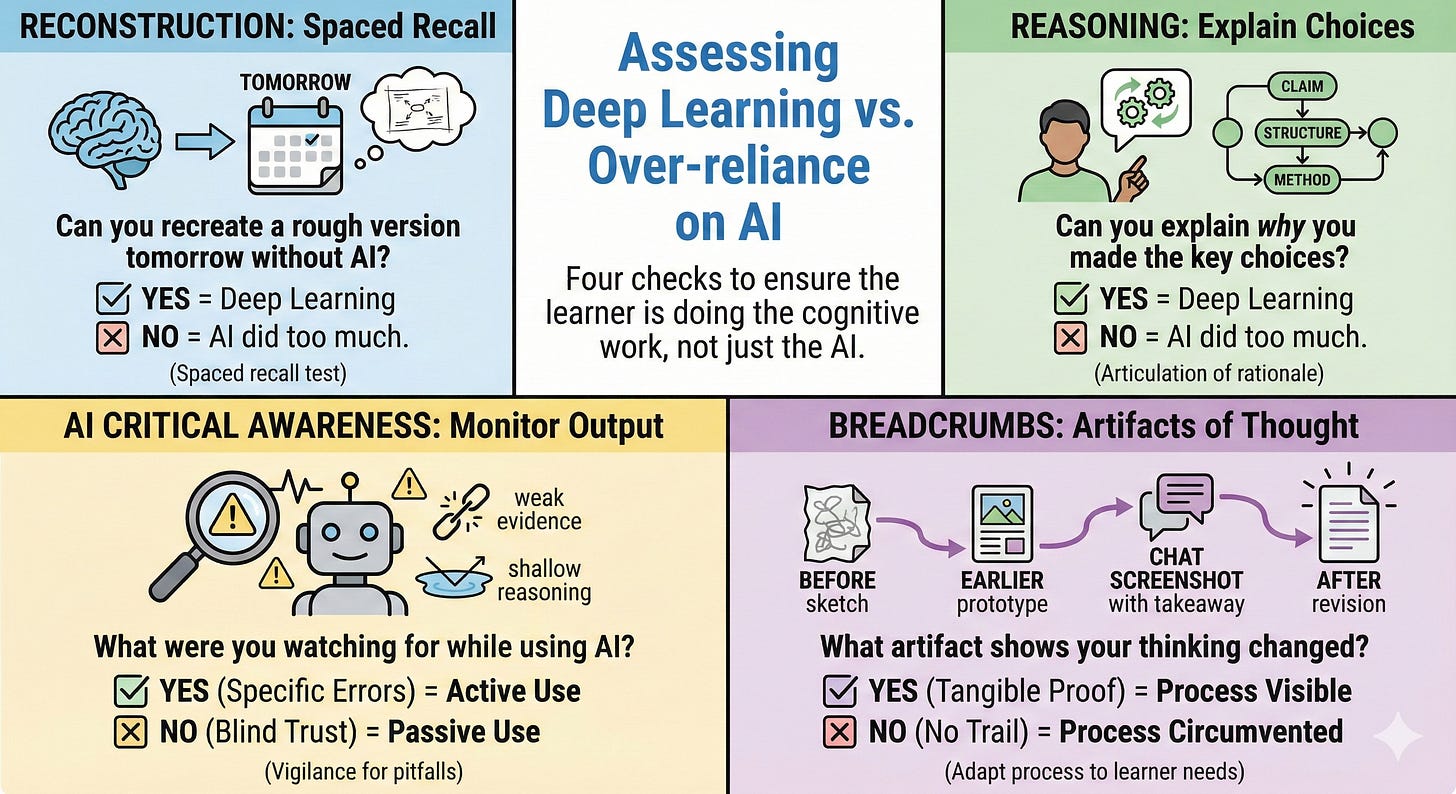

After some brainstorming, I wanted to point out a few ways teachers could have a quick chat with students as a diagnostic to see if their students might have taken cognitive offloading to the point where they have cognitive debt.

Reconstruction: Could you recreate a rough version tomorrow (spaced recall) without the use of AI? If you can’t, AI might have done too much.

Reasoning: Can you explain why you made the key choices (claims, structure, method, etc.)? If you can’t, AI might have done too much.

AI Critical Awareness: What were you watching for while using AI (hallucination, weak evidence, shallow reasoning, tone mismatch, etc.)? If you can’t, you were using it AI blindly.

Breadcrumbs: What artifact of learning shows your thinking changed (a before/after sentence, a sketch revision, a chat screenshot with your takeaway, an earlier prototype)? If you can’t answer it, AI might have circumvented a step the process, or the process is not serving your needs. Consider adapting the process according to the learner’s age and needs. If adaptation of the process is necessary, dialogue with the learner about how they will record their learning.

When it comes to friction leading to learning, it’s also important to note that not all friction is created equally. Productive struggle is the kind that can lead to students feeling curious through a guiding question, solving a problem that they care about, exploring something they’re curious about, seeking feedback and making adjustments to their work, spaced retrieval, etc. For more on effort, read this fantastic article from Carl Hendrick, what it is, and how to help students engage in it.

What we really want to avoid is unproductive struggle, like unclear instruction, difficulty seeing the board because of seat placement, high stress levels, language barriers, boring topics, insufficient background knowledge, etc. These sorts of frictions are not stimulating or engaging and can hamper the learning experience. For more, I would recommend exploring the UDL framework on how barriers can be dropped for all learners. It’s also worth noting that productive struggle is an equity issue in many schools around the world. When we have barriers related to AI access, language proficiency, AI skill, etc., some students may actually have a privilege to overcome barriers through their use of AI. As the UDL framework encourages, we should be considering how we can remove barriers for all learners; if AI can help kids to translanguage, unpack classroom concepts, access further practice, I would wholeheartedly advocate for this approach.

Struggle is not equal to suffering or challenges in learning; productive struggle is about getting kids comfortable being in their own Vygotskian Zone of Proximal Development, and recognizing what it feels like (sometimes a little uncomfortable). Forgive another metaphor, but it’s much like going to the gym. We do not ask our personal trainers to lift the weights for us because we know, our muscles won’t grow without the effort, and we have to choose the right amount of weight that we can lift to push our muscles. Our lessons that push each learner to grow without unproductive barriers while intentionally using AI that maintains important forms of effort is the point. Teachers who address AI through dialogue with their students and establish clear processes and expectations are one way to make sure AI-use remains productive. Going back to the topic at hand, productive struggle often means taking time, and not necessarily completing a task efficiently.

Classroom dialogue ideas

How do we get really good at something; does AI help us to get better at things? Where is the effort in our work going to be placed with us as learners, and where will we think with AI? How will you know if AI is doing the work for us rather than with us? What could your effort look like in this task? How can you manage your time to make sure learning takes place?

End of Part 1. In Part 2: Practical Application

We know we want Iron Man, not Wall-E. We know we need to protect productive struggle to avoid accumulating cognitive debt. But knowing why is different from knowing how. If we stop here, we just have a philosophy, not a plan. In Part 2 of this series, I’m going to tackle the practical side: how do we move beyond the “process vs. product” debate and actually design processes that leave “breadcrumbs” of thinking? I’ll share specific strategies including the “Monday Ready” tools and an example from a classroom with a sneakpeak at the second edition of my book to help you design learning where students stay in the pilot’s seat.

Great Reads Related to This Article

These are some of the works I reference, allude to, or was inspired by while writing this article. All of them look at the ideas presented here from a different angle and are recommended reading in the form of articles or books.

“AI Is Changing How We Learn at Work” by Lynda Gratton

“Why Does Thinking Feel So Hard?” by Carl Hendrick

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

Doing School by Denise Pope

Mindset by Carol Dweck.

AI Disclosure

Parts 2 of this article was created through an iterative Think, Generate, Edit process, repeated multiple times. The initial draft was written by me and informed by my work on AI-Enhanced Processes, Second Edition. I then used multiple AI models: ChatGPT, Google Gemini, Claude Sonnet, and ChatGPT Deep Research. They were used to refine, challenge, and extend my thinking. Visual elements were generated with ChatGPT. All writing and final decisions were reviewed and edited by me, a real human, to ensure coherence, intent, and accuracy.

It’s also worth disclosing how long it took me to write this article. I would estimate 8-10 hours were spent writing, thinking, rewriting, generating, etc. I would not say that was a particularly fast way of working, rather AI was my collaborator.